Anger and Reality

"Somewhere or other, outside oneself, there was a 'real' world where 'real' things happened. But how could there be such a world? What knowledge have we of anything, save through our own minds? All happenings are in the mind. Whatever happens in all minds, truly happens." - George Orwell, 1984

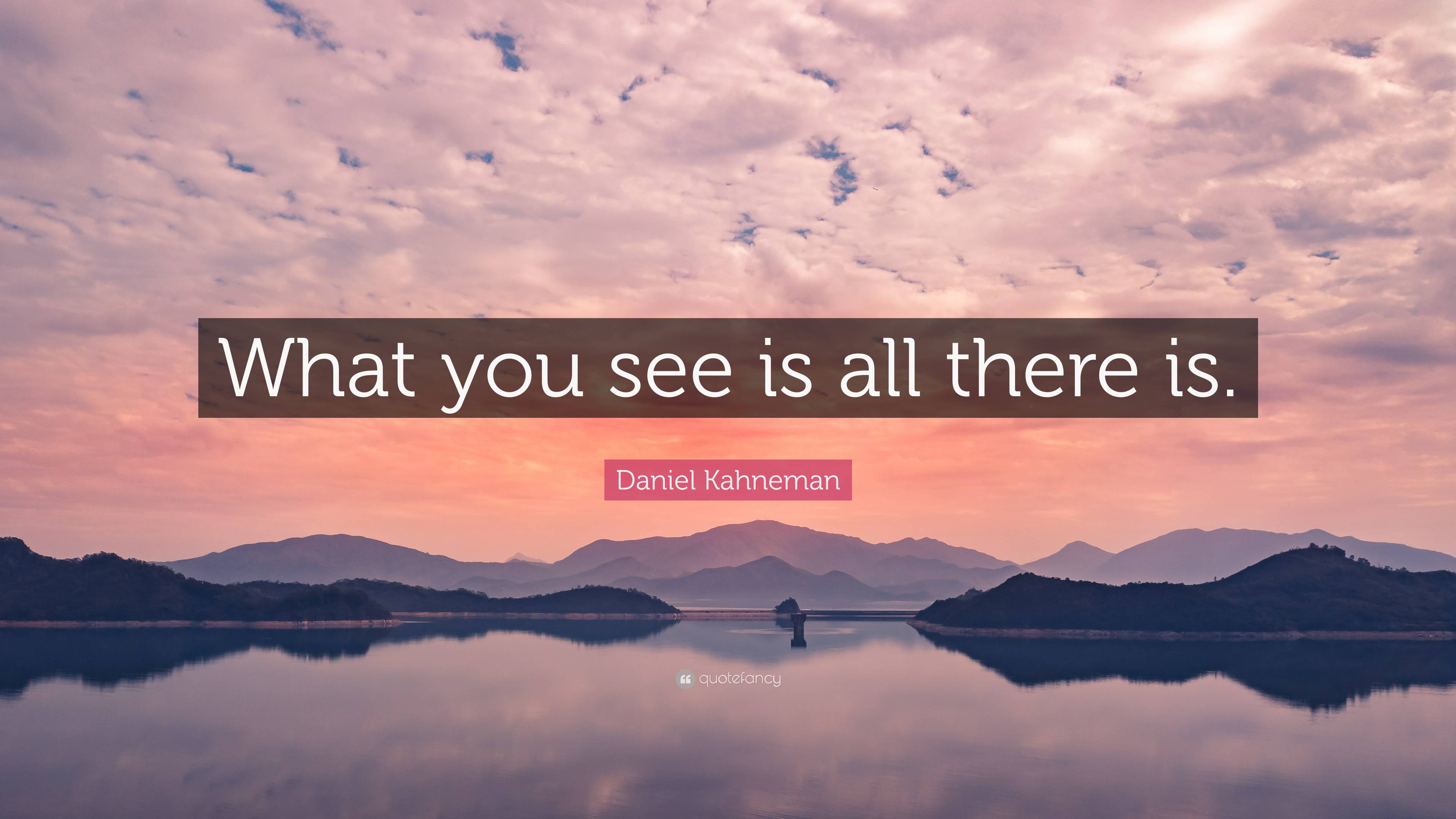

Everything that happens to us, has happened to us, or will ever happen to us, from the moment we become conscious to the moment we die, is mediated by our minds. Physical reality exists with or without us, of course, but we see almost none of it. The only reality that we'll ever know is our own subjective experience.

We understand the idea of subjective experience intuitively—two people witnessing the same event will have different experiences—yet we ignore its important consequence: we can drastically change our reality by changing our minds.

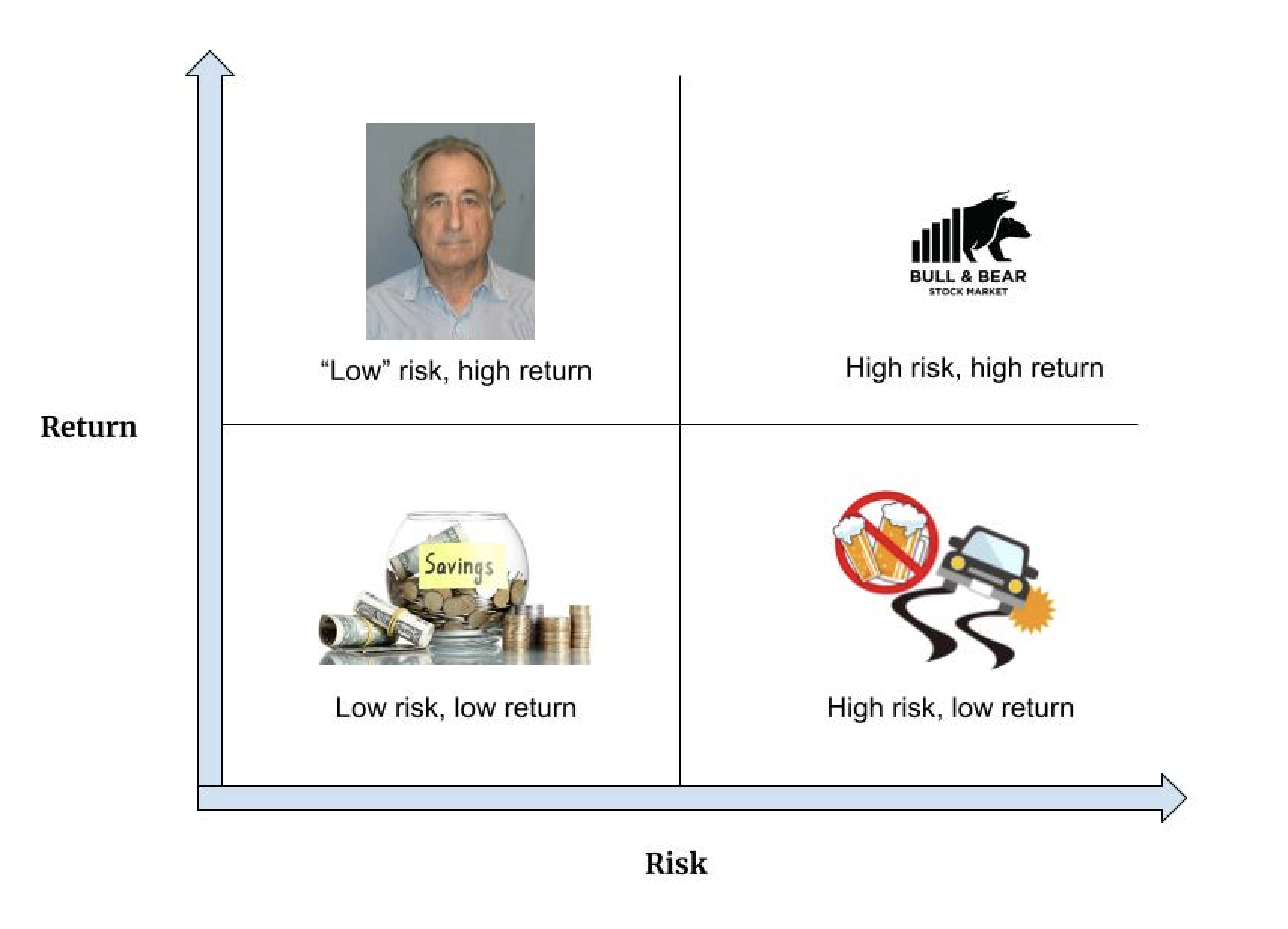

Unsurprisingly, our minds are rarely the first resort in our quest for peace and happiness. Instead, almost everything we strive for is an attempt to change ourselves ("If I lose 15 pounds I’ll finally be happy") or change the world ("If that baboon wasn't ruining this country then my daily life would be so much better"). When we do lose that weight, buy the Tesla, or celebrate the demise of the ruling party, we move the goalposts to the next target, and our baseline temperament stays the same.

Instead of changing how we view ourselves and the world, why do we look externally for happiness and believe that contentment is right behind the next milestone?

A primary reason is that "most of us are genuinely not aware that it is possible to change our minds," shares Sam Harris in his Waking Up app, which I also plugged in my last post. He calls this ignorance a "glaring cultural blindspot" that causes us to suffer unnecessarily. "It comes down to the simple ability to be able to recognize one’s thoughts as thoughts, as appearances in consciousness, and to no longer be their mere captive.”

Our thoughts and feelings filter the only reality that we'll ever know. We sometimes deprioritize this filter, but more often ignore it completely.

In another example of a major cultural blindspot, both Camel and Lucky Strike claimed to be the "doctor-recommended" brand of cigarettes during the 1930s and 40s. It's easy to laugh at the credulous smokers of that era, but it's hard to admit that we have blindspots of equal magnitude right now. "It’s possible for an entire society to be totally confused about something rather important," says Harris. "The fact that most people don’t know they are missing [mental practice] doesn’t make it any less of a problem for them or for the rest of society. More or less all of the world’s chaos, apart from natural disasters, is borne of our lack of insight into our mental lives.”

Just as the blindspot surrounding cigarettes led to millions of early and painful deaths, the blindspot around mindfulness has led to a hyper-reactive American culture. We are collectively angrier than we were 20 years ago.

(For what it's worth, it seems that ad-supported platforms like Facebook were the tipping point for the modern descent into anger. Once ads became the default way to monetize the internet, human attention became the most valuable resource, and companies—starting with social media, which bled into cable networks—quickly realized that the way to capture attention was to elicit fear in the oldest systems of our brain. Capturing attention meant more ads could be sold to more eyeballs, and nothing captured attention like outrage.)

If you watch cable news, go on Facebook/Twitter, or even sit in a grocery store parking lot, the frequency of outrage is impossible to ignore. Monetizing outrage is a dangerous self-experiment, and monetizers cannot feign ignorance towards the experiment, since the idea of inciting anger is not new:

“The rage that one felt was an abstract, undirected emotion which could be switched from one subject to another like the flame of a blowlamp,” wrote George Orwell in 1984, published over 70 years ago.

The challenge of reining in our emotional responses may not be new, but it becomes more existentially important every year (see: emotionally underdeveloped leaders of nuclear-armed countries making threats on Twitter). As sociologist E.O. Wilson once said, "The real problem of humanity is the following: We have Paleolithic emotions, medieval institutions, and godlike technology." Never has the need for a less-reactive, more empathetic, and more self-aware population been stronger.

I don't write this post to convey hopelessness or claim that I'm immune to outrage (I'm a very reactive person by nature, so I have to avoid the outrage platforms as much as possible). On the contrary, I believe that people are beginning to care—and teaching their children to care at an early age—about shepherding their own minds. People don't want to feel badly, so more are turning to Eastern philosophy (like meditation) to get a grip on themselves.

Meditation creates self-awareness, and self-awareness is how we begin to make the filter of our reality more apparent. A helpful analogy: if someone looks at a tree through a window every day for years, one day they might suddenly notice their own reflection on the window. The reflection was there all along, just as our thought patterns are here all along, waiting to be noticed.

When we feel the usual trigger of anger, for example, we can see the anger as anger instead of letting it blindly channel through us. This self-awareness then allows us to decide how long we want to remain angry. "It’s a superpower in modern times to be able to get off the ride of anger," to quote Harris one last time.

The bad news is that there is no shortcut to getting to know ourselves and our emotional patterns better. The worse news is that once we do get to know ourselves better, there is little comfort in transforming the reactive and learned emotions that we've fled to for decades. Despite the discomfort, self-awareness really is the gateway to both a peaceful life and the long-term survival of civilization.

In an era of ubiquitous anger, I hope that this post provides a path towards optimism: reducing reactivity and suffering can start with a single, deliberate pause. Before we try solve every problem in our lives, we can look within. There are no external barriers to changing our minds. The only barrier is awareness.