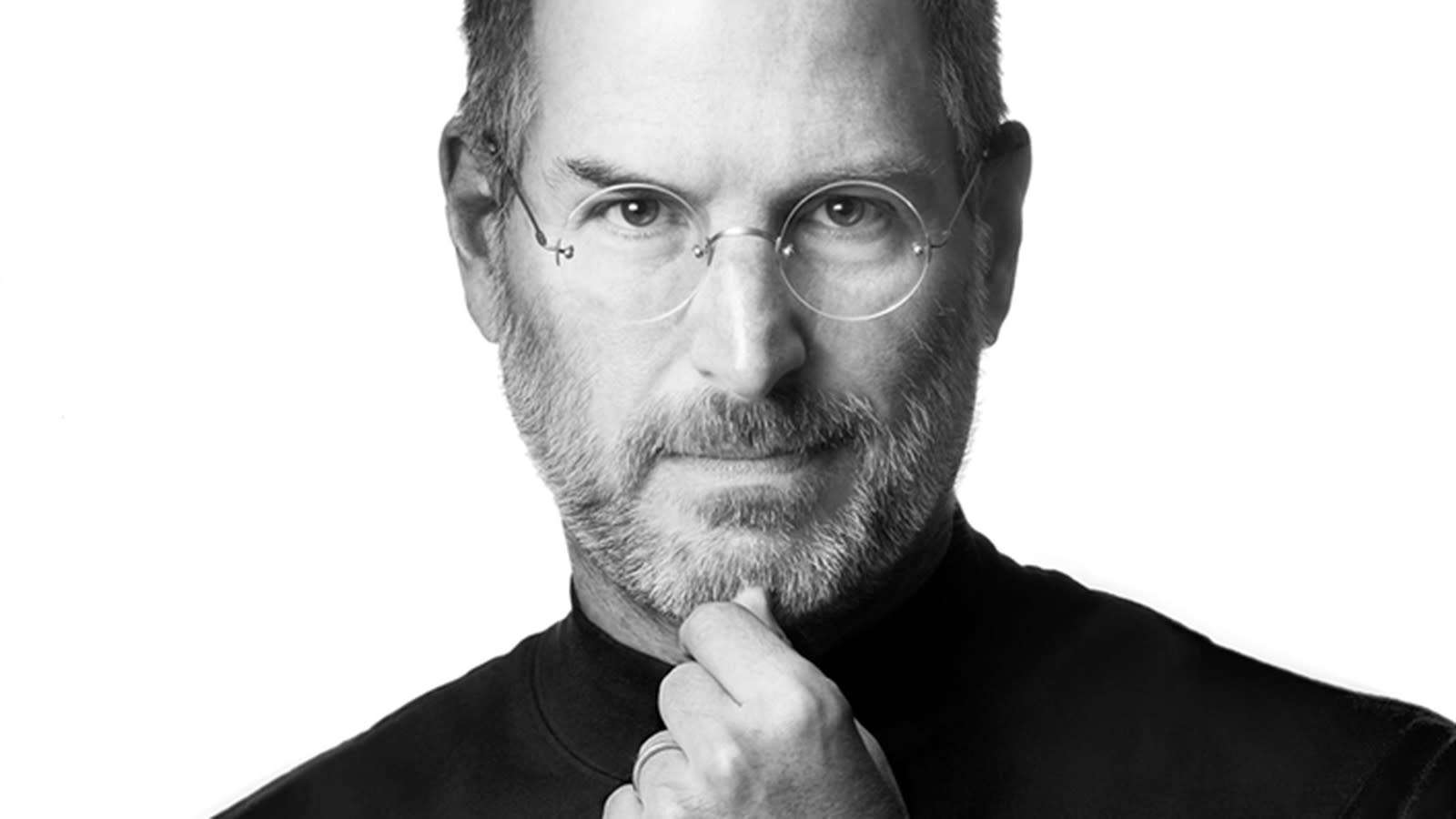

Steve's Jobs (Part I)

Recently, as part of the “other” quadrant of my life (football, other, work, sleep), I read Walter Isaacson’s Steve Jobs biography. I’m a big fan of Isaacson’s books. While living in Nashville, I reserved a seat to watch Isaacson speak at a local high school. As part of my 2019 plan to increase my street cred, I was going ask him to sign his Einstein bio that I own and love. I decided to bail on the engagement to join my new coworkers in the music industry’s annual Turkey Bowl, where I watched my trash flag-football teammates get blown out. (I take no responsibility for the defeat as they did not give me the ball. I regret both skipping Isaacson’s talk and making you read this paragraph.)

Anyway, Steve Jobs was a genius across multiple spectrums of intelligence. He was also brutal to people. As Isaacson writes, Jobs could “size people up, understand their inner thoughts, and know how to relate to them, cajole them, or hurt them at will. The nasty edge to his personality was not necessary. It hindered him more than it helped him. But it did, at times, serve a purpose” (565). Jobs’ brutality may have helped him force change and move quickly, but he still could have changed the world at Apple without leveraging his intelligence to viciously cut down subordinates during his mood swings.

Jobs was a control freak as well. He subscribed to bizarre “fruitarian” diets (e.g. only eating carrots or juice) on and off for weeks or months at a time. He also insisted that Apple control the entire user experience by restricting Apple’s operating system to Apple hardware. In other words, MacOS and iOS still only run on Apple hardware (Macs and iPhones), whereas Microsoft’s Windows and Google’s Android (for mobile) famously run on hardware from a ton of companies.

Though Apple’s strict integration of software and hardware has looked especially genius since the first iPod (a convo for another time), Jobs’ obsession with a curated user experience and the brutality to people around him stemmed from egotism and a compulsion for control.

Massively accomplished people like Jobs are just as flawed as the rest of us, and we should remember this when celebrating their contributions. With that in mind, I’ve been fixated on a few traits that allowed Jobs’ genius to shine. For this post, I want to discuss his “high agency” and ability to focus on “what’s important now?”

High Agency

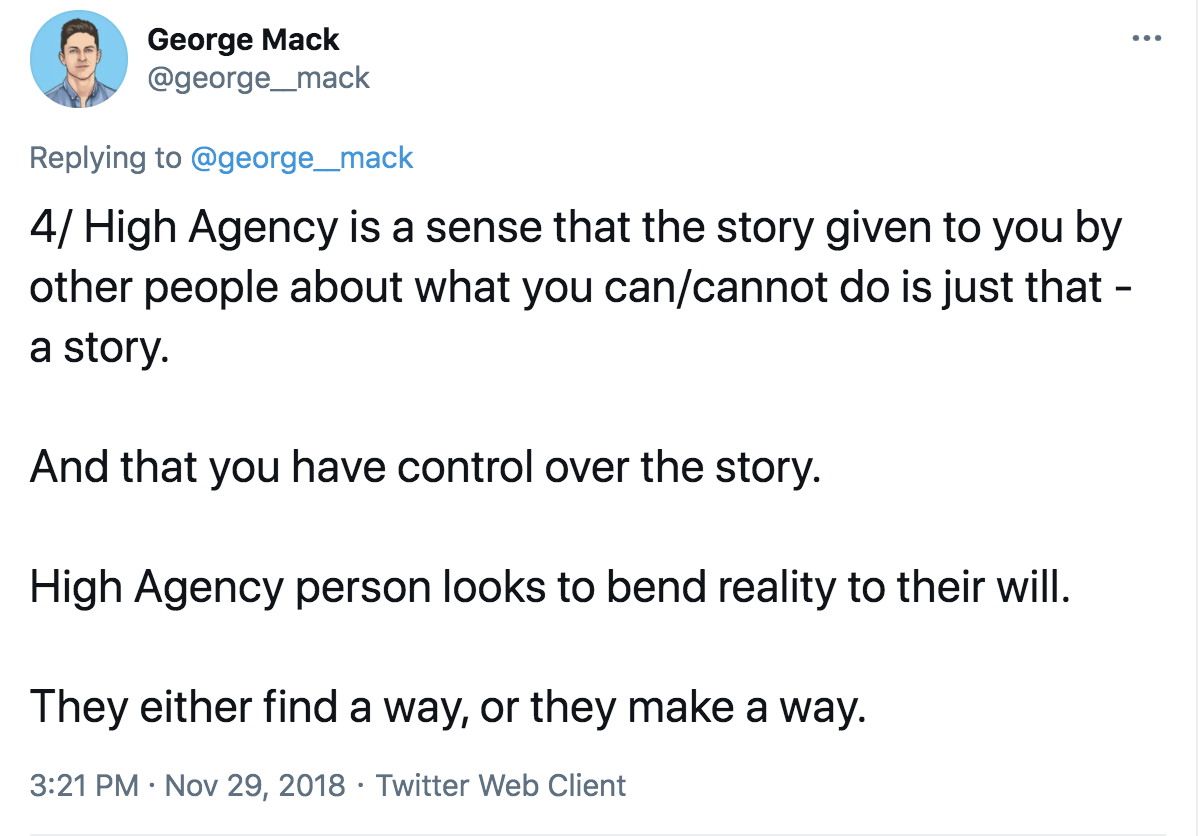

I came across the term high agency last year thanks to an excellent Tweet thread from a British dude I follow named George Mack. He defined it in the below Tweet.

Jobs demonstrated high agency his entire life:

*As a kid, he needed a missing part to build a frequency counter for his Explorer’s Club. He looked up Bill Hewlett (founder of HP) in the phone book, chatted with him for 20 minutes on the phone, got the parts, and worked at Hewlett’s plant after his freshman year of high school.

*Jobs dropped out of Reed College so that he could drop in on classes he liked without paying tuition. The calligraphy class that he came back to had a major influence on the fonts of all personal computers to this day.

*Eventually, Jobs left Reed’s campus, found a company called Atari (!) in the newspaper, and refused to leave their lobby until they hired him, despite being an unbathed hippie. This was his start in tech.

There are countless examples from his tenure at Apple where he made something amazing happen with limited resources. Jobs described this high-agency life philosophy in a 1995 interview, the greatest two-minute YouTube video this side of the 2009 Kentucky Derby.

My favorite snippet: “Life can be much broader once you discover one simple fact: Everything around you that you call life was made up by people that were no smarter than you and you can change it, you can influence it, you can build your own things that other people can use… Once you learn that you’ll never be the same again.”

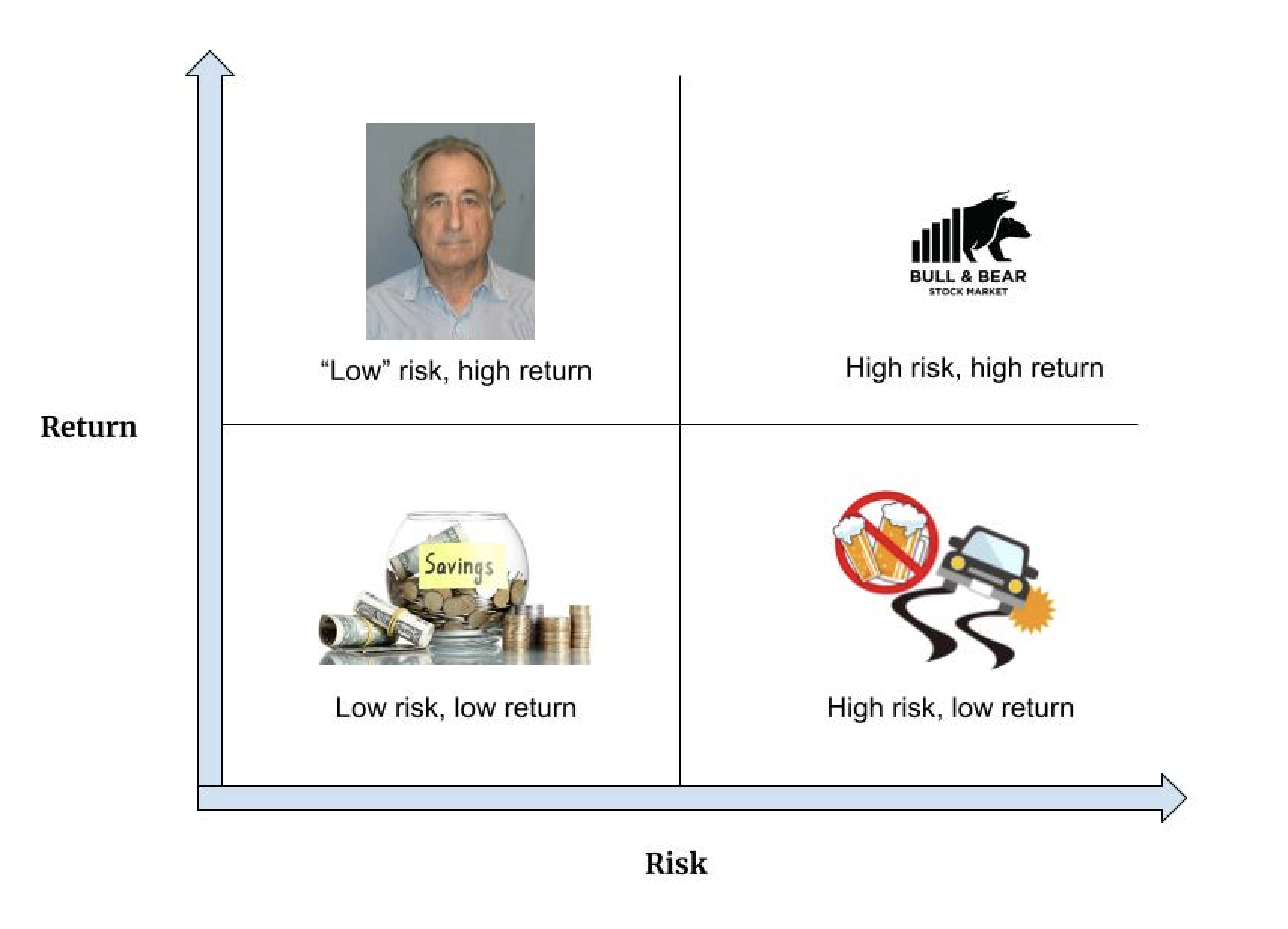

Social psychologists remind us that humans are loss averse because loss aversion helped our species survive. The cavemen that took crazy risks were more likely to starve or die, so those that took fewer risks passed on their genes.

We’re playing with different stakes now, yet we often take a “no” at face value and don’t question the stories that are told to us — we’re wired to avoid risks.

Steve Jobs didn’t operate this way, and he rewired his brain from a young age to see life as something he could change. To borrow a phrase from early Apple employees, Jobs’ “reality distortion field” drove his teams to be persistent, resourceful, and to find a way through or around obstacles that seem impossible. (It also, for what it’s worth, helped him manipulate people). He led a high-agency life.

What’s Important Now?

In 2015, my college roommate and I went on a leadership cruise hosted by our fraternity’s national org. I promise it was even weirder than it sounds. The keynote speaker was a celebrity dentist named Dr. Bill Dorfman, whom I couldn’t help but like despite his shameless embrace of being a mega-rich tool. (He also hilariously interrupted the other speakers during smaller sessions. In one instance, he interrupted a gentleman/etiquette presenter from the back of the room to remind the audience to never grab one’s crotch in public.)

One part of Dr. Bill’s speech that I still vividly remember was the acronym WIN — what’s important now? WIN, at the time, seemed terribly obvious and mundane. Every few months, however, WIN comes back to me when I realize that I spend 92% of my waking hours procrastinating on hard things by doing easier, less important tasks. If I actually followed the WIN advice, I’d probably be retired and hanging out with Bill on a beach.

Elon Musk and Steve Jobs

In one of my favorite stories, Elon Musk’s friend and investor, Steve Jurvetson, set up a 30-minute call between Elon and a NASA gene-sequencing expert to discuss sequencing (potential) life forms on Mars and beaming the data back to Earth. Elon turned down the phone call, saying it could wait a few years and that the call was irrelevant until the Falcon Heavy rocket could fly to orbit. That level of focus and ability to ignore what is not immediately important is abnormal, but also shared by Steve Jobs.

Jobs’ obsession with simplicity in his products was reflected in his ability to simplify and prioritize the collective focus of Apple. Jobs refused to let the company stray from the top two or three priorities at any time. As now-Apple CEO Tim Cook said, “There is no one better at turning off the noise that is going on around him. That allows him to focus on a few things and say no to many things. Few people are actually good at that.”

When we try to stay on top everything, we go an inch deep and a mile wide and get nothing real done. I’m definitely guilty of this, and it’s a product of how I / we consume and live in 2021. It’s hard to say no, which is part of what make Musk and Jobs outliers. (Golf take: I hope Rickie Fowler comes across Dr. Bill’s WIN advice. We’ll sadly see him in fewer commercials, but he will start winning again.)