Teaching Myself Economics

Both homo sapiens and aliens like Giannis Antetokounmpo evolved to live in a world of manageable complexity. For more than 99 percent of human existence, large social networks numbered in the dozens, not the millions. Since these social networks didn’t reflect the scope of our world today, we have to use mental shortcuts to cheat our biology and get by. Our internal biology and modern external reality are not evolved to mesh.

We listen and watch “experts” explain why events were inevitable or why something will happen soon, and most of us forget that they are as clueless as we are. I forget this. The ability to understand each of the trillions of factors that lead to a single event is not part of our repertoire. It would be as far fetched as Bobby Petrino understanding human emotions.

We cope and avoid insanity by oversimplifying; talking heads and politicians oversimplify when they explain Brexit or how the Raptors won—it’s because KD and Klay were injured, not because the ball bounced perfectly on the rim against the Sixers. We even oversimplify when we’re asked why we chose our specific career. We point towards a childhood passion or college major, overlooking the subtle (and even overt) pressures and nudges all around us.

Oversimplification itself is not a problem as long as we’re aware that we do it, but things quickly turn ugly and tribal when this awareness is lost. Even worse, people in power know how attracted our brains are to simple explanations, so there is an incentive on both political sides to use generalizations against us (Think “Obama wants your guns” (from the Right) or “Supporting any border security means you’re racist” (from the Left)).

A clear-cut example of this is the collection of postmortems on the 2016 U.S. presidential election. If Trump received a few thousand (on a scale of 130+ million) fewer votes in a few states (out of 50), opportunistic armchair experts would not reduce a complex event (albeit with a very simple, winner-take-all result) to singular explanations like a xenophobic lash, a Russian hack, or rust-belt panic in the face of automation.

The frustrating aspect of these “hot takes” is not that they’re wrong. It’s that all of these takes can be true or partially true at the same time. Racism and xenophobia exist. So does automation in the midwest. So does Facebook’s unprecedented social reach. And populism, and Hillary’s popularity compared to Obama, and the fact that if any of the dozens of factors are removed, Hillary probably wins, and history unfolds differently.

History is not inevitable: our human brains are not good at seeing the past or future as one result amidst an infinite array of possibilities instead of a linear sequence in which we obviously would have seen Trump coming if we had just seen the signs. The future is nothing more than a huge probability tree, and if I’ve learned anything from sports, it’s that the most likely outcomes don’t always happen.

You wouldn’t describe yourself using a single adjective, so why would we describe something much bigger than our personalities by using a single explanation? Because we live in an attention economy where the loudest voices are paid more than the most rational or actionable voices are paid, and because discussions of politics (like religion) involve identity—when identity is involved, people become tribal and emotional.

Partisan politics make me cynical because otherwise smart people reduce billion-input events into a single cause. They have an incentive (in money and attention) to do so, and our primal brains crave it. It’s manipulative, yet it’s our default way of looking at the world. If the goal is actual social progress, outrage and generalizing are not the ideal first step.

A better idea is putting our idealism into action, taking responsibility, and fixing ourselves before we try to fix society. Society is nothing but a million individuals, and generalized blame won’t reverse the stagnation (and recent decline) in American life expectancy or solve disparities in racial economic outcomes, even if the blame wins us social points.

It’s more important than ever to discuss complex issues in a constructive way. Sadly, ignoring nuance and making divisive topics black-and-white is the name of the game in 2019. Ironically, when we ignore nuance and make blanket assumptions, we borrow a page directly from Trump’s own playbook.

An unintended consequence of this orgy of outrage is that people become altogether disillusioned by a specific subject and shut down before they attempt to understand it—not unlike a kid initially who likes a sport but is criticized by a parent until he/she decides to turn to rebellion (aka graffiti and procreation).

We have to start at the very bottom if we want to avoid oversimplifying. Topics like healthcare are complex and scary, so it’s easier to pretend we know the answers than to understand the system. I, for one, neither have the answers nor understand how the system actually works.

Next time you’re trying to stump someone in a heated debate and start using cheap tactics (I usually revert to jokes and anger), ask yourself if your opinion is merited. For me personally, the more I fear exposing my ignorance on a subject, the more I revert to personal attacks and generalizations (now take these interactions and remove all decorum and you have 98% of social media interactions between strangers).

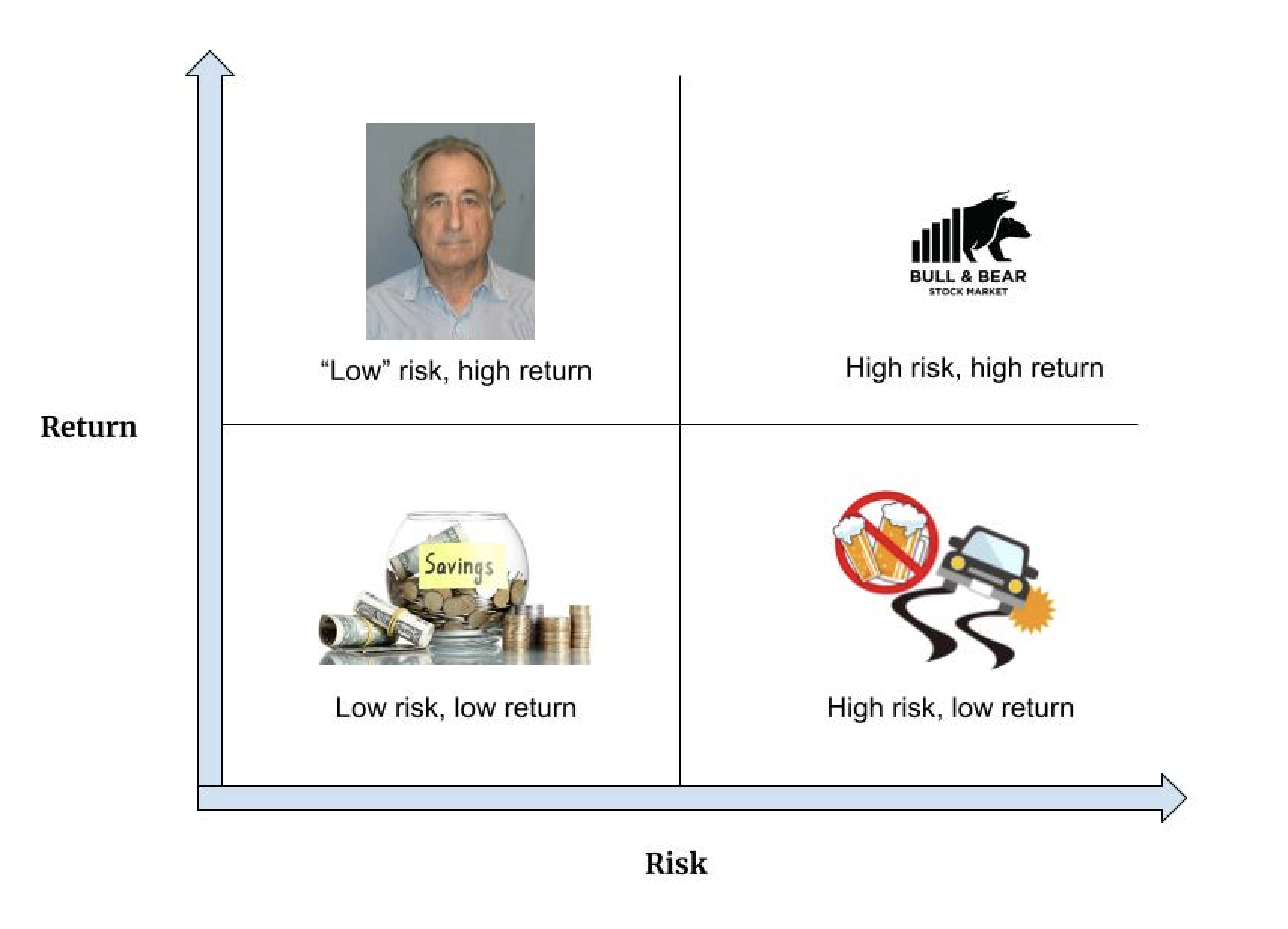

Fundamental understanding is rarely gleaned from school and only comes with effort. Sadly, effort is hard to magically conjure. We need nudges, incentives, and powerful habits to avoid depleting our willpower. Recently, I moved to the United States of America and realized that I’d like to understand money, the economy, and personal finance so that I don’t continue my college trend of exclusively investing in Bitcoin. I then panicked because I know very little about personal finance, money, and economics (and Bitcoin, SMH).

In classic 2019 fashion, the inundation of advertisements (investment companies, mutual funds, banks, ED pills) and buzzwords that I was too lazy to actually learn (APR financing, adjustable-rate mortgages, the Big Short) overwhelmed me, so I needed to learn the basics. Also in 2019 fashion, I had the entire collection of human knowledge inside my laptop. I had come to the right century!

I read Naked Economics, by Charles Wheelan, and felt marginally better in my ability to understand something as simple as how do banks make money? (the most basic way: they charge you more money on loans compared to the money they give you to hold your money). I’ll briefly discuss a few topics in which I have a new opinion as a result of my recent perusing.

For the first time, I uncovered some apolitical realities about economics that struck a chord with me. Also:

I am new to this, so what I write is far beneath many of you, like if I read a blog post on someone who stumbled upon the NFL and wanted to share their thoughts on the Cleveland Browns “2019 powerhouse.” If I say something that might be factually wrong, send me an email so that I don’t lose my money and walk around like the people who think the Browns have been good since 2002.

At least one FDR will learn something new, so I guess it’s worth it. Also you’ve read this far.

The Ideal Tax Rate for Americans?

My former assumption: I really had no idea what to think. I grew up hearing conservatives pseudo-sexually eulogize the Reagan years (and produce frat-star progeny who wore “Regan-Bush ’84” sweatshirts around campus) for the genius of supply side economics, and I often hear the New Left remind us all that top marginal tax rates were over 90% during Dwight Eisenhower’s presidency. I thought that it would be nice to fund programs like Social Security and renewable energy initiatives without destroying the millennials (or the earth), but I also didn’t want America to turn into Venezuela.

What I now think: Cutting a high tax rate can actually boost government revenues up to a point, which is counterintuitive. Per Wheelan, this actually didn’t happen with Reagan or George W. Bush due to the low starting point of the tax rates. (Although the revenue levels were raised, they weren’t raised relative to what the revenues would have been in the absence of a tax cut. We can’t forget inflation!)

It seems to me that some Republicans wrongly believe that supply-side economics implies that “any tax cut increases revenues” and pays for itself—as John McCain argued in 2007. It also seems to me that some Democrats think that a 90% marginal tax rate would have no effect on America’s economic growth. I also believe that an ultra-high marginal tax rate negatively affects total productivity and the total size of the economic pie.

It basically comes down to whether we want to maximize the size of the economic pie or the size of each person’s slice of a smaller economic pie: per capita income is higher in the US than in it is in France, yet we have a higher proportion of kids living in poverty (per Wheelan). I now believe a middle ground is best—aka somewhere between Trump’s 37% and Bernie’s 90% top rate—but I’m more likely to be struck by lightning than see middle ground in 2019.

Why Trump’s Protectionism is Bad

My former assumption: Protectionism makes everything more expensive (since there is less competition) and limits our growth (there are fewer cheap resources if we can’t use competitive overseas labor and resources), so a big factor in the 2016 election was Trump (successfully) avoiding the reality of jobs lost to automation and overall growth by trumping-up people’s fear of immigrants and portraying them as job thieves. Economic progress leads to ‘creative destruction,’ so I preferred the idea of government-funded retraining programs over regressive measures like steep tariffs on many imports.

What I now think: The above part about Trump trumping up false fears hasn’t changed, but a reality that struck me is that protectionist measures are the exact same measures we use to punish unruly nations. When we want to punish countries like Iran, we use trade restrictions to bully them. So why would we turn to protectionism unless the workers affected by ‘creative destruction’ disproportionately vote for us? We wouldn’t. Per Wheelan: “Even in the short run, The Economist thinks that the tariffs we placed on Chinese steel and aluminum will destroy more jobs than they create due to corollary industry effects.” Also, cheaper goods (from global competition) have the same effect as higher wages.

I think that we will inevitably face even more income inequality as technology and automation can replace non-information workers. If high-paid knowledge workers represent a smaller voting bloc than the opposition, it is in their own best interest to not alienate the rest of America and have a string of populist presidents.

On Sweatshops

My former assumption: Sweat shops are horrible and the people working there would rather be doing anything else. The only reason we let Nike get away with it is because we like their shoes.

What I now think: As The World Counts notes, “If workers’ rights are respected sweatshops can actually help poor countries. For example, in Honduras, the average clothing “sweatshop” worker earns 13 US dollars per day, yet 44 percent of the country’s population lives on less than 2 dollars per day.” Assuming the labor is done humanely via ‘fair trade,’ American capital investments not only help a developing nation as a whole, but they also provide highly competitive wages for unskilled workers. I know this is not what our hearts want to hear, but people would not work in sweatshops if they had better alternatives.

Why not pay them much, much more than we do now since we have the funds? Because advanced American technology means that the only way to make sweatshops advantageous for Western producers is to have cheap labor. In other words, if a robot can do work at 1/3 the price of an American worker, then sweatshop labor would need to be 1/4 the price of an American worker to make it financially rational. Surely there is room for increased wages in sweatshops, but only up to a certain point: once the crossover point is reached in terms of cost-cutting, then the whole factory will close—hurting the local people and their economy. It’s paternalistic and insulting to automatically assume that we as Americans know what is best for foreign workers and their lives.

And finally…

The US-China Situation

My former assumption: I am compulsive and want a balanced budget in my life, so I thought we start paying off the debt to China and everyone else. Looking at huge debt numbers makes my heart palpitate—my recurring nightmare is missing the first 10 questions on Jeopardy and curling up in a ball underneath the podium.

What I have learned: Most of this info comes directly from Naked Economics: When the US is heavily indebted to another country, the debt would typically self-correct since the US dollar would depreciate. In other words, if foreign nations own lots of US dollars, the supply of USDs will exceed the demand, so the value of the USD goes down relative to the trading partners’ currencies. Capital is like an apartment: the greater the supply, the cheaper the rent (this is how the FED lowers interest rates, I learned.)

American exports would become more competitive and imports more expensive with a weaker dollar, which gradually narrows the current account deficit (since we’d sell more goods and services relative to what we buy).

The Chinese government has an export-led growth strategy that depends on keeping its currency (the yuan) pretty cheap. It reinvests a lot of its earnings into US Treasury bonds. China wants to shift the balance of power as it slowly strengthens the yuan, yet it doesn’t want to destroy the dollar since its savings are mostly held in USD that it couldn’t pull out in time if the dollar collapsed. As an amateur, I have no idea how long this can go on, but I think it’s actually worse to be China since their debtor conveniently controls the US dollar. And since their best basketball player is still Yao.

Alas, when I look at this section and the protectionist section, I get confused, so I will stop.

Be well.