We Are Not the End of History

Declaration of Independence

In the cutthroat, polarized climate that much of the Western world faces at this moment, there are moral panics, reactionary movements, backlash against reactions, and general distrust between people of differing beliefs. Each side believes that the other is fundamentally wrong in its belief system, and that if other side could just leave its ideological dark side then peace and harmony would reign supreme. This is simplified, but the general idea is that the left and right in America fundamentally disagree on ideas of morality; unlike fiscal policy disagreement, there is rarely a middle ground in social debate.

I try to identify with neither political party (sorry, Communist Party of Mexico). I do this not to prove a point, but instead to make me happier. By happier, I mean I no longer have an emotional reaction when fifty percent of America viciously attacks the other side, because it’s not a part of my identity. When my identity is attacked, I feel bad, so I decided a while ago to heed the advice of Twitter prophet Naval Ravikant and associate my identity with as little as possible. The less I identify with, the less I’ll emotionally react to other people being mean, and the easier it is to change my mind on an issue when I learn more or when the facts change. That being said, please do not criticize Dwayne Sutton or Chris Mack for a few days. I need a safe space.

Claiming independence still allows me to have an opinion on a few things I feel strongly about, like environmental destruction and eliminating the designated hitter so teams can warm up between innings and make MLB games watchable again. Something I realized after removing party identity is that many opinions I had were only because I felt like I needed to have one. For example, if I tried to explain why Obamacare is good or bad in practice I would be completely talking out of my booty.

I say all of this because I want to zoom out on the whole debate of modern morality and acknowledge that this debate is entirely based on the 2019 time bubble we live in. In sixty years, the moral landscape will be totally different, yet it’s much easier to avoid thinking about this. Before diving into that idea, I hope that the preceding paragraphs convinced you that I am writing this from an apolitical perspective (just kidding, it's the perspective of the Mexican Communist Party), and the only thing I try to express are personal ideas.

Reasonable People?

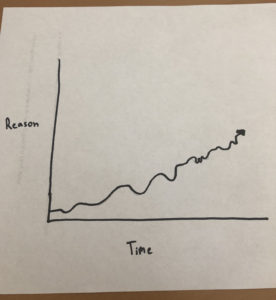

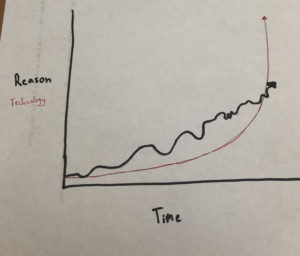

I like to believe that humanity’s collective reason and social progress follow a similar path of progress to the stock market. It’s not a constant upward trend, nor is there exponential growth like that of technology. Instead, it’s a slow march towards the top right corner with the destiny of becoming more reasonable over time. Even in this decade of terror from white nationalists, religious extremists, etc. all over the globe, I believe that we’re more reasonable as a species than we were in 1980.

This work of art—backed by my very accurate data—demonstrates the lack of constant growth in society’s rationality. Instead of a big step every year, we seem to be on a one-up-two-big-steps-down-then-slowly-eking-out-two-more-steps-over-a-period-of-five-years pattern. Maybe we’ve only made one or two steps forward this century, but historically the progress has been undeniable. Just ten years ago the US was led by a more stable administration, but concepts like decriminalizing certain substances or reducing prison sentences for non-violent offenders were years from reality. Even if the world has taken reactionary steps back since 2016, I doubt that anyone would say that the world of 1990 was more empathetic or connected (or as people outside of Mexico say, ‘woke’) than that of 2019. Hence, progress is slow and painful, but it has always happened on the bigger time frame.

With this in mind, I’d like to acknowledge how much we’ve progressed since 1953. In 1953, the civil and women’s rights movements existed only on the horizon, McCarthyism suspended human rights, and the environmental movement did not remotely exist. Even the idea of a self-determining nation was still up for debate, for 50 of 54 countries in Africa were still ruled by colonizing nations. The only important constants between 1953 and 2019 are Queen Elizabeth II, Betty White, and Vince Carter dunking.

If we’ve come this far since 1953, we’ve come twice as far since 1887, an era in which it was recently deemed moral that humans were not property. And it wasn’t a sweeping realization. It only took ~700,000 American deaths and having states believe that they were solely fighting to preserve the Union to help free a race of people. So, as you can imagine, the people of 1953—living in the post-WWII and post-New Deal boom of the 1950s—probably thought that they had “figured it all out” compared to the people of 1887.

But what will the people of 2085 think of us? Surely we’ve figured out social justice after the centuries of white patriarchy turned out to not be fair after all. Now we just need to make sure we implement the best current plans to end discrimination and achieve a living wage for all and the people of 2085 will look upon us as the generation that finally figured it all out. It sure is nice to be the special ones.

Tangent

The scary thing about technological progress is that it evolves much faster than our morality and reason. These concepts, long as humans don’t have computers in their brains, move only as fast as biology allows, which is why it’s the inconsistent and slow upward march. Now compare that graph to the exponential improvements of technology.

Sixty years of technological innovation on our current path will create a world that we cannot comprehend (assuming we overcome unpleasant odds and do not destroy ourselves and the earth in the process, which is not a safe assumption). The television show Black Mirror is a mind-blowing glimpse into the future, but the people (and robots) of 2085 will look at Black Mirror like we look at The Twilight Zone—aka we’d rather just watch Chef’s Table.

This is why it’s scary to put technology that is exponentially better than the humans of 1945 in the hands of humans that are only a few steps more reasonable than the people of 1945—the people who first used nuclear weapons. We (as in everyone who is not the US president or North Korean dictator) now realize that nuclear weapons are a terrible idea, but will we be able to control technology that is 10,000 times more advanced with a brain that is only a slightly more reasonable?

Special Ones

Back to being the “special ones:” one of the hardest thoughts to believe is that we’ll quickly be just as wrong right now as the people of 1953 are to us. And for the humans who live in the sixth-biggest city on Mars in 2140, the people of 2085 will look dumb and we’ll look like the people of 1887. Nobody wants to look like the people of 1887. The problem is that it’s impossible to know how our morals will evolve on that time frame. Imagine explaining the issues of social media to President Grover Cleveland.

This inevitability of human morality evolving (as long don’t kill everyone or accidentally end civilization) is easy to forget in the technology bubble in which we live in 2019 where everything seems like genuinely important news. But this inevitable upward-right progress is exactly why I dislike presentism.

Presentism

Per Wikipedia, which is a free encyclopedia, presentism is “the anachronistic introduction of present-day ideas and perspectives into depictions or interpretations of the past.” In other words, presentism is when we apply modern morality to past events and judge people and cultures based on our current morality and not the collective morality at that earlier time. It’s easy to rag on someone who is not as far up the reason graph as we are, for we obviously have the advantage of being born today. After a decade of playing cello, you wouldn’t judge early versions of your cello-playing self with the same expectations as you have today, but that’s essentially what happens when we discuss historical figures.

A common critique of people who denounce presentism is that in avoiding moral judgments, we are practicing moral relativism (per Wikipedia, a free encyclopedia). Their argument is that morals are timeless even though our “mores” change, so moral relativism is dangerous ethically. I think that having a moral compass is vital, but the history of humanity shows that morality itself has pretty clearly been relative. AND, relative morality is actually a positive as long as we become more reasonable over time and don’t devolve.

But isn’t the whole point of moral progress to acknowledge the failings of previous people? I believe acknowledging the horrible practices and false beliefs of history is fine, but discounting someone’s entire person for a single belief or practice seems like we are denying the context of the time. I think we would live in a better world if we focused on applying modern morality to the modern world. Society is usually not a friendly place. Better to acknowledge our progress and try to make it much (more) better than to pass judgment on everyone before us. If our kids will judge it all differently anyway, does it not make more sense to notice the mess in our own lives/world and address that?

School?

I am not arguing that slavery, genocide, and later forms of intolerance are fine or that we should not acknowledge historical atrocities. I am instead trying to raise awareness that today’s collective morality will not be the morality of tomorrow, and if we try to airbrush history so it fits the morality of today, we’re playing a dangerous game. This does not mean we should only teach history from the perspective of the “winners” and colonizers, but it does mean that we should not discount 100 percent of someone’s contribution in shaping the modern world solely due to his/her immoral behaviors.

If this pattern of presentism continues, the people of tomorrow will pass sweeping moral judgments on not only what we do today, but also that which society of 2019 has already judged. In other words, future people will both judge us and revise our current judgments to fit the social mores of that future point in time. All of history would be catered to the prevailing group consensus of the present moment, which is a denial of how people of previous ages experienced reality. For example, if fossil fuels are deemed immoral, it would be incorrect to say that most people of 2019 felt morally wrong every time they drove a car.

If everything that happened that runs counter to what’s socially acceptable in the present is censored, how can we possibly expect to learn from the past? For example, it’s becoming more common to protect students from writers who expressed racist views. Is it not better to let these writers serve as a glimpse into a hateful context that we’ve left behind so that students can understand why tolerance is important?

It’s necessary to show the perspective of both the oppressor and the oppressed so that students can understand how frighteningly easy it is for a group of people to believe they’re in the right. In other words, if we only show the perspective of historical victims or historical villains we’ll miss out on an important life lesson for students: people are easily corrupted by power and often don’t realize that—in the eyes of future generations—they are the villains.

The Point

Back to the point of this two part post: remembering that we’re wrong too. It is much easier to look back at the past and question how stupid we could be than it is to look forward and question what it is that we’re doing now that will be judged as stupid and bad.

I think that this is a blindspot for most people in general, and I personally find it much easier to cringe at younger versions of myself that to be objective and honest about my flaws today. It hurts my ego more to accept honest criticism than it does to hear criticisms of me at age sixteen. I doubt that I am alone in feeling this.

Now apply this feeling to American or Western culture in general. It’s easy to sit here in 2019 and wonder why it took so long for the minority of Americans who opposed gay marriage before 2015 to finally relent and let the majority prevail. Then I remember that the majority of Americans did not support gay marriage as recently as 2011. Even Barack Obama, one of the most significant presidents ever, flipped his public opinion until finally supporting gay marriage permanently in 2012. Will he be remembered as an opponent to social justice?

George Washington is the only president who freed all of his slaves, but he is still a slaveowner. Even these examples of iconic leaders in American history are fallible humans like us. Power did not magically vault them a century ahead on the moral progress line.

This fallibility, in my opinion, does not automatically make someone evil. There is obviously no aspect of slavery that needs to be debated, but does this mean that we should we remove the Washington Monument? Washington’s opinion on slavery was more moral than that of presidents 70 years later. Should we disinvite Obama from speaking engagements since he publicly was against gay marriage when he entered the White House? GW and Obama were aligned with the majority opinion of their country/state before they woke up and shifted to what history would show is the proper moral belief.

Conclusion

All of this leads me to the question that I came here to address: what widely-accepted practices of 2019 will be considered morally wrong in the coming decades? Even if we don’t continue today’s practice of presentism, it is obvious that we’ll appear tragically wrong across several aspects of our daily lives. Soon, I’ll dive more deeply into one of these practices—factory farming. I know I won’t be right about many of these opinions, but I also know that what we do today won’t be considered right either.